A rare find indeed!

A rare find indeed!

Matt Edwards: Collections Access Assistant, Derby Museum and Art Gallery.

The Enlightenment! team have recently purchased a rare barometer that came up at auction following its discovery during a house clearance in Borrowash, Derby. I went down to Bamfords auctioneers on the sale day and found myself in quite a fierce bidding war with an internet and telephone bidder. It was quite a day, not for the faint hearted. There was some local media attention prior to the auction and certainly afterwards as to who the purchaser was. The general feeling among the local collectors was that they hoped it was staying locally and that the buyer was a museum. Well done us!

The John Whitehurst angle barometer inscribed ‘Whitehurst/1757’ in a Mahogany case with a silvered scale is the earliest recorded angle barometer of this type with his patent 0-60 scale. This is the second earliest surviving instrument of the 25 known to have been manufactured by John Whitehurst. Of the 24 others 1 is lost and 4 are untraced. Only 11 however are dated.

Conservation

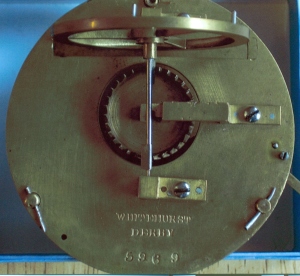

The images you see here are of the barometer in the condition in which it was found. My next job was to seek conservation advice. The main issues were the missing veneers, the blockages and possible damage of the mercury tube, a missing finial at the end of the arm (which adjusts the indicator which is also missing) and the general strengthening needed to the angled joint.

In correspondence with a specialist in barometers I have gained some knowledge about their fixtures and fittings but I also thought it might be worth looking at a similar model to make some comparisons. Derby Museums were to take trip to Oxford to visit the Ashmolean so I took the opportunity to go to the Museum of the History of Science to look at a Whitehurst angled barometer in the collection there. While this was a fine example in much better condition, there was little provenance and it was less unique being undated. It was however useful to see the missing parts and take photographs to pass to the conservator. Although some conservation work was necessary we still wanted to keep the barometer true to its original state without too much intervention, therefore preserving it as a historical object.

Look out for updates and new photographs after the conservation treatment.

Who was John Whitehurst?

John Whitehurst (1713 – 1788) was born in Congleton, Cheshire. Apprenticed to his clockmaker father, together they would go for walks in the nearby Peak District, during which time a life long interest in geology was developed. He set up a clockmaking shop in Derby in 1736, where he built up a business of national recognition, including providing movements for Matthew Boulton’s manufactories (Whitehurst wrote to Boulton in 1757 offering to make him a barometer, but there’s no way of telling if this is the one). His sidereal clock of 1772 which showed the movement of the sun in relation to fixed stars is considered one of the most significant clocks made.

In keeping with the times, Whitehurst took an active interest in several areas of engineering technology: he was a mechanical and hydraulic engineer; he made compasses, pyrometers, barometers and timers for pottery kilns; and he undertook major domestic engineering improvements (plumbing, heating systems and kitchen ranges) at Clumber Park, Nottinghamshire.

An active member of the Lunar Society, he introduced Joseph Wright of Derby to this circle, and his portrait by Wright hangs at Derby Museums and Art Gallery.

In 1774 he was appointed Keeper of the Duplicates or Copies of the Standard Weights of the Royal Mint. Now living in London and continuing his investigations he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1779.

His most significant publication was An Inquiry into the Original State and Formation of the Earth in 1778. In it he proposed a method to predict which rocks might exist beneath those close to the surface, using detailed sectional diagrams of the strata of Derbyshire to support this. He described the fossil sea creatures, and speculated on their age, having to resolve the intellectual difficulties in reconciling this geological evidence with his Christian faith.

In 1787 he published his final work An attempt towards invariable measures of length, capacity and weight from the mensuration of Time, seeking to rationalize all forms of measurement by decimalization.

Recent comments